Patch Management at Scale: How to Update Windows and Linux Without Breaking Production

Patching is one of the highest ROI security controls—yet it’s also one of the fastest ways to break production if done poorly.

In mixed environments (Windows + Linux + cloud + on‑prem), patching often becomes:

-

a monthly fire drill,

-

a spreadsheet-driven process,

-

or “we’ll do it later” until an incident forces your hand.

This article outlines a practical patch management approach you can roll out in real infrastructure: predictable, auditable, and designed to minimize downtime.

Why Patch Management Fails in Real Ops

Inconsistent inventories

If you can’t answer “what systems exist?”, patching becomes guesswork. Shadow VMs, old endpoints, and forgotten servers create blind spots.

Unclear ownership

“Who owns this server?” is a common patch blocker. Without service ownership, patching stalls.

One-size-fits-all windows

Patching “everything on Sunday night” ignores business criticality and dependencies.

No verification loop

Many teams patch, reboot, and move on—without validating service health, kernel versions, or application behavior.

Patch Management Goals (What “Good” Looks Like)

A mature patch program should deliver:

Predictability

-

Fixed cadence for routine updates

-

Defined emergency process for critical CVEs

Risk-based prioritization

-

Critical internet-facing systems patched first

-

Lower-risk systems batched later

Minimal disruption

-

Rolling updates

-

Maintenance windows aligned to service needs

-

Automated prechecks/postchecks

Evidence and auditability

-

Patch status reporting

-

Change tracking

-

Exception handling with expiry dates

Step 1: Build a Reliable Asset Inventory

What to capture

-

Hostname, IP, OS/version, kernel/build

-

Environment (dev/stage/prod)

-

Criticality tier (1–4)

-

Owner/team and service name

-

Patch group (e.g., “prod-web-rolling”)

Practical sources

-

AD + SCCM/Intune (Windows)

-

CMDB (if accurate)

-

Cloud APIs (AWS/GCP/Azure inventory)

-

Linux tools (e.g., osquery, landscape, spacewalk equivalents)

-

Monitoring/EDR platforms (often best truth source)

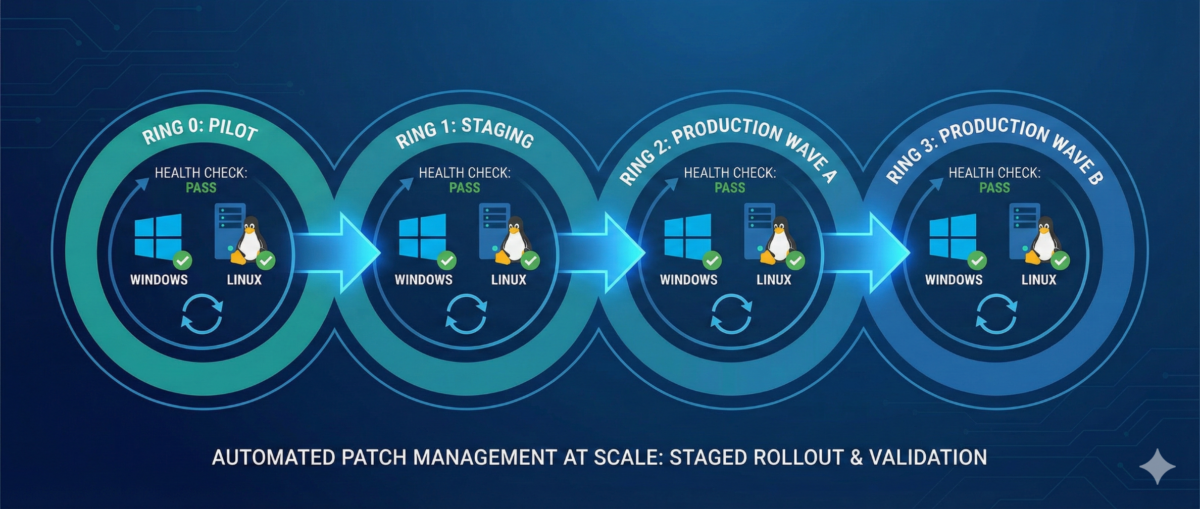

Step 2: Define Patch Rings and Maintenance Policies

Patch rings reduce blast radius.

Example ring model

Ring 0 — Lab/Canary

-

First patch landing zone

-

Includes representative app stacks

Ring 1 — Low-risk production

-

Internal services, non-customer-facing nodes

Ring 2 — Core production

-

Customer-facing workloads with rolling capability

Ring 3 — Critical/Stateful

-

Databases, domain controllers, cluster control planes

-

Heavier change control, deeper validation

Service-based maintenance windows

Instead of one global window:

-

align patching to service usage patterns,

-

and use rolling updates where possible.

Step 3: Standardize on Tooling Per Platform

Windows (common patterns)

-

Intune / WSUS / SCCM / Windows Update for Business

-

GPO for policy enforcement

-

Maintenance windows tied to device groups

Key practices:

-

staged deployments (rings)

-

automatic reboots only in controlled windows

-

reporting for “installed vs pending reboot”

Linux (common patterns)

-

configuration management (Ansible/Salt/Puppet/Chef)

-

distro-native repos + internal mirrors

-

unattended-upgrades (carefully) for low-risk groups

Key practices:

-

pin critical packages if required

-

kernel update strategy (reboot coordination)

-

consistent repo configuration

Step 4: Automate Prechecks and Postchecks

This is where patching becomes safe.

Prechecks (before patching)

-

disk space and inode availability

-

pending package locks / broken deps

-

snapshot/backup status (where applicable)

-

service health baseline (CPU/mem, error rates)

-

cluster state (no degraded nodes)

Postchecks (after patching)

-

OS build / kernel version updated

-

reboot completed and uptime as expected

-

service is healthy (HTTP checks, synthetic tests)

-

logs show no startup failures

-

monitoring confirms normal KPIs

Step 5: Reboot Strategy Without Downtime

Stateless tiers: rolling restarts

-

drain one node at a time

-

patch + reboot

-

verify health

-

re-add to pool

-

proceed to next node

Stateful tiers: controlled approaches

-

leverage replication/failover where possible

-

patch secondaries first

-

promote/demote intentionally

-

schedule longer windows and validate data integrity

Step 6: Handling Critical CVEs (Out-of-Band)

When a critical CVE drops:

-

Identify affected assets quickly (inventory is everything)

-

Prioritize internet-facing and high-privilege systems

-

Patch canary first (short validation)

-

Roll through rings with accelerated windows

-

Document exceptions with deadlines

Step 7: Reporting, Exceptions, and Compliance

Metrics worth tracking

-

Patch compliance % by ring and environment

-

Mean time to patch (MTTP) for critical CVEs

-

Reboot compliance

-

of exceptions and time-to-expiry

Exception policy (must-have)

If a system can’t be patched:

-

require risk acceptance approval

-

define compensating controls (WAF, isolation, hardening)

-

set an expiry date (no “forever exceptions”)

Conclusion

Patch management isn’t “install updates.”

It’s a repeatable operational system:

-

inventory → rings → controlled rollout

-

automation → verification → reporting

-

exceptions with deadlines, not excuses

If you run Windows and Linux at scale, patching can be both fast and safe—but only when it’s treated like an engineered process.